Basic Facts

Capital: San Jose

People/Customs: Population is about 4.9 million. Most Costa Ricans, or “Ticos,” are mestizo, descended from Spanish settlers and natives, but Costa Rica is a multi-ethnic country. There are still some indigenous tribes living in Costa Rica.

Language: Spanish is the official language; local dialects are also spoken, like Bribri, Patois, and Mekatelyu.

Climate: Costa Rica has a tropical climate with two distinct seasons: dry season (December to April), and rainy season (May to November), temperature and precipitation are affected by elevation and two bodies of water, the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea.

Food/Farming: Costa Rica’s most important crop is coffee. There are also large rice, banana, and sugarcane plantations. Costa Rica also produces cattle for beef and dairy, poultry and eggs, teak wood, beans, palm oil, oranges, mangoes, pineapples, and other fruits and vegetables. A typical Costa Rican meal, or “casada tipica,” consists of meat or chicken, rice and beans, tortillas, salad or roasted vegetable, and fried plantains.

Government: Costa Rica is a democratic republic with a constitution defining three branches of government. The current president is Luis Guillermo Solis.

Currency: Costa Rican Colόn, or CRC. It takes 573 CRCs to make $1 USD.

Art/Music/Culture: Costa Ricans usually learn to dance at an early age. Merengue, salsa, cumbia and dub are the four main Costa Rican dances in addition to traditional folk dancing with costumes. Over time, Spanish beats mixed with the indigenous tunes and made a new kind of music special to Costa Rica. Local artisans produce crafts like decorative oxcarts, wooden carvings, pottery, leather work, and jewelry. Holidays celebrated in Costa Rica include: Christmas, New Year’s Day, Easter and Holy Week, Fiesta de Los Diablitos, Independence Day on September 15, and Labor Day on May 1.

History

Before Christopher Columbus came to Costa Rica in 1502, there were hundreds of thousands of natives from different tribes. There is archaeological evidence that they traded with other tribes in the lands of North Central America and South America. When Columbus “discovered” Costa Rica, he was on his fourth trip to the New World. He confronted a hurricane, was blown off course, and landed in Costa Rica. He traded with the natives and claimed to see more gold in 2 days than he had in 4 years on Hispaniola–that is how Costa Rica, or “Rich Coast,” got is lasting name. It became a Spanish Colony in the 1560s, but San Jose was not established until 1737. By then, the Indian population had been all but destroyed by disease and hard labor, and only a few tribes survived in the jungle.

For the Spanish, Costa Rica did not live up to its name because its wealth is in the cultivation of the rich volcanic soil and not in mined minerals. Costa Rica’s history is also unique in the Caribbean because it never had a slave-based economy. Instead, smaller self-sufficient farms of the Central Valley became the precursor to a rural democracy. However, as in all the other Spanish colonies, society was ruled by men, with power being held by white landowners and the Catholic Church.

Spain ruled Costa Rica until September 15, 1821, when they became independent. Costa Rica separated from Spain peacefully, but without Spanish control, conflicts inside the country arose, leading to a short civil war. The Liberals gained control, moved the capital to San Jose, and joined the CAF, Central American Federation. In 1824, the Nicoya-Guanacaste province left Nicaragua and joined Costa Rica. While other Central American countries struggled with long, bloody civil wars, Costa Rica remained relatively peaceful and was able to focus on agriculture and infrastructure.

When it was discovered that the highlands of the Central Valley were perfect for growing coffee, the government subsidized the planting of saplings. By the mid-1800s, Costa Rica was growing and processing coffee for European markets. By the century’s end, coffee represented 90% of the country’s exports. The coffee processors, rather than plantation owners, became the country’s ruling elite.

In 1890, the first railroad was completed by an American railroad man, Minor Keith, in order to transport coffee to the coast. He planted banana plants along the tracks, which he eventually began export to the United States. The fruit became so popular that by the end of the 1900s, banana exports surpassed coffee, and Costa Rica became the world’s top banana producer. Banana money bought power—the United Fruit company controlled local politics and communications. But in 1913 a disease struck the banana plantations and ended the powerful monopoly.

Despite following the normal Central American pattern of dictatorship and civil war in the first half of the 20th century, Costa Rican leader Jose Figueres Ferrar established the world’s first unarmed democracy (meaning Costa Rica has no military) in 1949. Costa Rica got dragged into the conflicts with the United States and Nicaragua in the 1970s, but the elections of 1984 reaffirmed their commitment to peace. President Oscar Arias later won the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in negotiating a peace plan which ended the conflicts.

After the rise and fall of coffee and bananas, the most valuable resource of Costa Rica turned out to be the wilderness itself. Starting with a nature conservation area in 1963, the “Green Economic Revolution” began with a few tourists coming to see the rainforest, but now about one-third of Costa Rica’s land is preserved as nature reserves, wildlife refuges, and national parks. It has a successful tourism-based economy, with people coming from all around the world to enjoy the natural beauty the country has to offer.

Land forms/Flora and Fauna

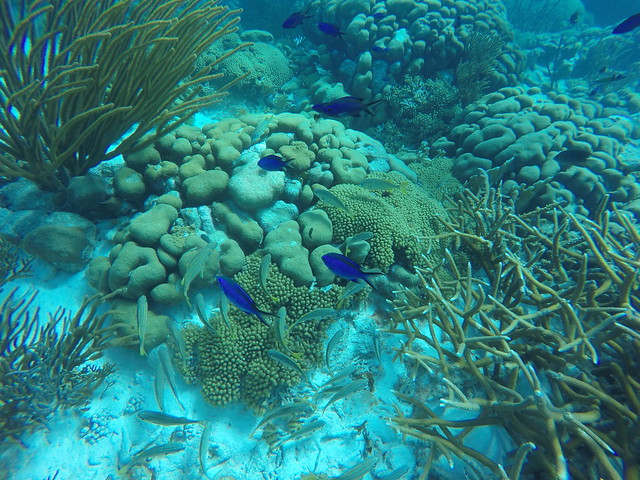

Costa Rica is bordered by Nicaragua to the north, Panama to the southeast, the Pacific Ocean to the west, and the Caribbean Sea to the east. Costa Rica has 51,060 square kilometers (19,714 square miles). It has cloud forests, mangrove wetland, rain forests, desert, beaches, pastureland, volcanic mountains, and coastal farmland (banana and pineapple plantations). It is known for its diverse flora and fauna. Native birds include: the Scarlet Macaw, toucans, hummingbirds, Magpie Jays, Quetzals, Blue-crowned Motmots, and Northern Jacanas. Some of the mammals are Spider monkeys, Howler monkeys, Squirrel monkeys, sloths, Pacific Spotted Dolphins, Pumas, Margays, Pygmy Anteaters, Capuchin monkeys, Tapirs, Jaguars, many species of bats, Humpback whales, and Coati. There are also Caimans, Jesus Lizards, Leatherback turtles, Eyelash Viper snakes, boa constrictors, and many species of frogs, as well as insects and arachnids like scorpions, tarantulas, Blue Morpho butterflies, stick bugs, and fireflies, to name a few.

Things to do

Surfing on the Pacific side (Guanacaste Province), ficus tree climbing in Monteverde, night walk in Monteverde Cloud Forest (Curicancha Reserve), white water rafting, kayaking in rivers or mangroves, coffee tour in the mountains, Arenal Volcano National Park (hanging bridges, hot springs, and ziplining), Bat Jungle in Monteverde, waterfall tours, horseback riding, nature hikes in Manuel Antonio National Park or Corcorvado National Park, and other wildlife tours and refuges.

Bibliography

McCarthy, Carolyn, and G. Benchwich, J. S. Brown, J. Hecht, T. Spurling, I. Stewart, L.Vidgen, and M. Voorhees. “Costa Rica,” Central America on a Shoestring. Lonely Planet Publications, 2013.

For more information, look at these websites:

https://www.costarica.com/travel/geography-of-costa-rica/