Anyone who knows me at all knows that I am chicken-hearted. I look at danger and run for the hills. Eli says that I am the kind of person that can turn a perfectly-fun activity into a life-threatening situation. (Arguably, I could say the same about him!) I have an uncanny knack for imagining the worst possible scenario. I go straight there, do not pass go, do not collect $200. When one of the kids gets hurt, Jay has to remind me to stop planning the funeral. And it’s not just a “mom-thing;” I have always had a nervous disposition.

If I operated according to my natural instincts, we would still be living in a ranch-style house with a white picket fence in a quiet little suburb. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but I would certainly not be pursuing my dreams. While my instincts are to live a small, safe life, my dreams are the opposite—I want to try everything, to go everywhere, to talk to everyone. I’m like Aladdin’s genie-in-a-lamp: “phenomenal cosmic powers, itty-bitty living space.” I have written about this dichotomy—and about my greatest fear: regret. This is what drives me to live despite my fear. And every time I experience something new, I have to confront that fear and decide whether to heed or ignore it.

For example, I climbed up, but decided not to jump from Morgan’s Head in Providencia. I don’t even like jumping from our high dive, where there is no rocky outcrop to surmount or coral heads to avoid upon landing. (The kids thought the 30-foot jump was great fun.)

But I did go ziplining in Panama because I wanted, just once, to know what it was like to jump out of a perfectly good tree and go screaming through the jungle. And, while I have enjoyed snorkeling or SCUBA diving (both of which involve breathing), I have never liked freediving (which involves not breathing). At the same time, I love to watch my kids take a deep breath, swim down into a sandy canyon between walls of coral, and glide comfortably at 10 meters/33 feet or more below the surface, for a minute or two. I sometimes follow them down, to take a closer look at something on the reef, but I get below the surface only a few feet before I begin to feel panicky, like I must get to the surface immediately to breath open air.

So, when the opportunity arose to take an Apnea Total class at Freedive Utila, I signed up along with Jay, Eli, Sarah, and Sam. Aaron opted out (he’s not much of a water kid) and agreed to keep an eye on Rachel while we were in class for a couple of days. I had no depth goals, really, but wanted to conquer my fear of holding my breath underwater so I could enjoy adventure-snorkeling with my family more. Jay and Eli have good breath-holds and are comfortable at greater depths, but Jay had trouble equalizing the air space in his ears past 12 meters/40 feet, and Eli wanted to learn about practicing safely. Sarah and Sam both like to freedive and wanted to improve their skills.

Freediving is a sport with many faces. We recently watched Le Grand Bleu/The Big Blue, an 80s film by Luc Besson about two divers who practice no-limits freediving, an extreme sport where divers compete to go deeper and deeper, using whatever means available. (The current record-holder is Herbert Nitsch of Austria, who dove to 214 meters/702 feet.) The film is interesting because it explores two sides of freediving: the desire to go deeper and find the limits for the human body, and the equally strong desire to see and understand what life is like in the ocean and to get closer to our mammalian neighbors beneath the waves. But if you have seen that film, then you may have gotten the wrong idea about freediving.

Most freedivers are not ego-driven maniacs who risk everything to go deeper. Most are using only their breath, a descent line, and maybe a pair of fins to safely reach depths of 100 meters/330 feet or more. Often, freediving is a means to an end, to go underwater unencumbered by SCUBA gear and explore reefs and wrecks, to go spearfishing, or to experience the Zen calm of descent and the emotional rush of coming back to the surface. And, like any sport, there is the challenge of training one’s body and mind and the fun of doing something you couldn’t do before, always improving and besting your previous depth or breath-hold.

Initially, it seems counterintuitive to go down and down into the deep blue while holding one’s breath—after only a few seconds, the build-up of carbon dioxide signals your brain that it is time to exhale, and after that the diaphragm begins to spasm. We’re land mammals, after all, only distantly related to the whales, some of which can swim down thousands of feet and hold their breath for an hour or more. But we share some interesting adaptations with these cousins and have only discovered our potential by pushing the limits. The human body is a well-designed machine—capable of much more than we demand of it. With training and breathing exercises to improve relaxation and gas exchange, it is possible within only a few days to improve breath-hold, and to dive deeper and more comfortably than one thought possible. (If you’re interested in freediving, I can recommend a book we read: James Nestor’s Deep.)

Of course, there are risks, too. Hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) can cause loss of motor control (sambas) and blackouts—rarely at depths, but more often in shallow water as a diver ascends, or at the surface after a dive. Pressure can damage the ears if one doesn’t properly manage equalization of air spaces. This is one reason we took the freediving class—to better understand and mitigate the risks. I have been snorkeling with Eli and watched him go down (deeper than I can follow) and disappear into an underwater cave or tunnel, then waited for him nervously at the surface for what seems like forever. Invariably, he comes calmly gliding to the surface, unaware of my discomfort. Preventing accidents and learning what to do if things go wrong was one of the best parts of our 2 1/2-day class. Already we have changed the way we practice freediving so that we take better care of each other and enjoy safer, more-relaxed snorkeling adventures.

Oddly enough, the biggest discovery in the class was that learning to hold one’s breath is, ironically, all about breathing. We spent a significant amount of time during class and in the water just breathing. Having practiced yoga in the past, I was familiar with some of the exercises, like belly-breathing or lengthened exhales, and with the benefits of certain kinds of breathing to the nervous system. When one practices a “breathe-up” at the surface before a dive, it is not hyperventilation, like you might imagine—this only increases tension and decreases safety. It is instead a pattern of deep, slow breaths which induce an almost meditative state that helps one prepare for a stress-free descent. Freediving is all about relaxation and the careful management of oxygen supply. Efficiency is everything; one wants to expend the least amount of energy so that one has more time underwater, either to reach a greater depth, or stay longer at a desired depth. And an anxious brain is a big oxygen-consumer, so learning to calm and quiet one’s thoughts and lower the heart rate makes a big difference. To some degree, it is all in your mind.

Watching my kids prepare for a dive was like watching them fall asleep as babies. Having spent their whole lives around and in the water, they have a comfort that I envy. Observing their dives was one of my favorite parts of the class.

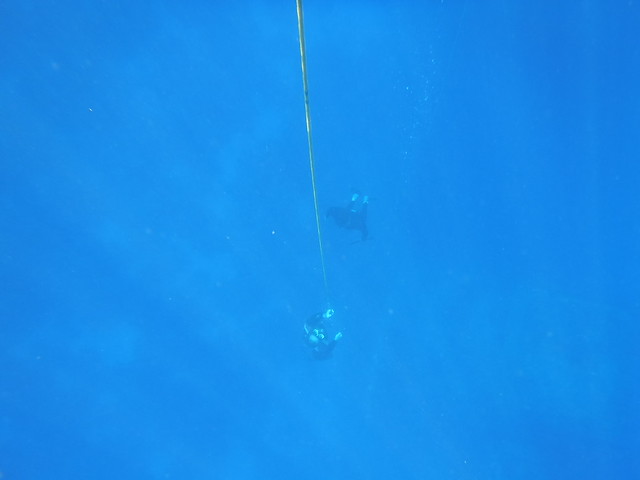

Going down myself was more challenging. Even at the end of the first day (when I managed to get down to 6 meters/20 feet), I still felt my heart rate accelerate before the dive, experienced discomfort during the dive, and was ready to come up before I’d reached half-way down the line, the bottom of which was at 12 meters/40 feet. When our instructor, Mariano, asked how I felt, I said, “Happy to reach the surface and breathe again.” He was incredibly encouraging and positive, and offered helpful advice after every dive. And he said the next day would be better.

He was right. The second day, I ignored the goal entirely (the end of the line was at 21 meters/70 feet, which Jay reached easily) and focused on quieting my thoughts and relaxing in the water. Having worked through my fear and learned that I could safely ignore my body’s message to “Breathe now!” for at least a minute, I was able to pull myself down the line, relaxed with eyes closed, to 10 meters/33 feet. Most importantly, I was able to do this without that familiar feeling of panic. Coming back to the surface, as my lungs expanded, I experienced euphoria. I began to understand why people say freediving can be addictive.

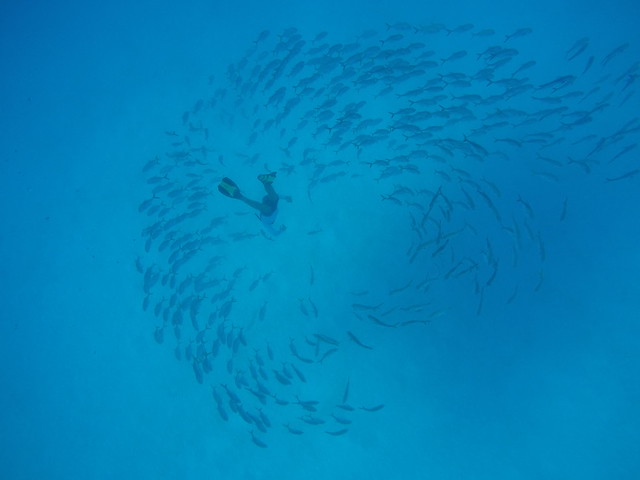

Class completed, we got in the dinghy the next afternoon and took our new skills out to the reef. The weather was calm, the sunshine bright, and the water crystal-clear. I love that feeling at the surface when I first get in the water with my mask on, like I’m flying, looking down on coral canyons, rays swimming along the sandy patches, fish darting in and out of rocky caves, the water gradually changing from turquoise to violet-blue as the reef drops off into the inky depths. First one, and then another, of our family dropped down to glide along the bottom of a trench, or down along the reef wall at the drop-off. Each person had a partner at the surface, watching to make sure he was safe, and each took the careful steps of a breathe-up at the surface to make going to depths more comfortable. I also dove down, gliding along a sandy canyon-bottom, like an airplane flying low, looking at the ripples in the sand and getting a close-up of colorful fish at home in forests of coral. I came to the surface, happy to take some recovery breaths, but no longer afraid.

What follows is what I wrote in my journal about fear as I mentally prepared for diving the second day.

Fear

Warns me of danger.

Keeps me from repeating bad experiences.

Makes me aware of risks and consequences.

Helps me to stay on the straight and narrow.

Keeps me alive.

But fear

Can cripple me

Can keep me from experiencing

Adventure, discovery, friendship, love.

Is the enemy of faith, the destroyer of hope.

Prevents me

From making progress,

From achieving my goals,

From fulfilling my potential.

Keeps me from really living.

Fear:

What should I do with it?

Name it:

What exactly am I afraid of?

Look at it from all sides:

Is it legitimate?

Is it keeping me from danger or preventing progress?

Should I listen to the warning, or silence the alarm?

Pray about it:

What does the Spirit tell me?

Do not let your heart be troubled.

I am with you always.

Perfect love casts out fear.

If I speak to God about my fears,

He can quiet my thoughts or confirm a warning.

Make a choice:

Allow it to keep me away or proceed with caution.

Keep it in bounds.

Do not be ruled by it.

Make decisions using logic, comparing risks and rewards.

Do not live each day under its shadow.

Do not listen to the thousand whispers,

but search for the one clear voice of reason.

Fear

If I do not master it, it will master me.

Final thoughts, from Psalm 139

Where can I go from Your Spirit? Where can I flee from Your presence? If I go up to the heavens, You are there; if I make my bed in the depths, You are there. If I rise on the wings of the dawn, if I settle on the far side of the sea, even there Your hand will guide me, Your right hand will hold me fast… Search me O God, and know my anxious thoughts. See if there is any offensive way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting.